This essay was written part way through Spore’s development, and summarizes one of the biggest transitions the project made — unknown to many — from what could have been a SimEarth like game/science toy to a capital-G computer Game. It tells how Spore made some of its early, and most crucial, navigational decisions down the branches of design possibility, to use Will’s own language. I feel like a discussion of how Spore turned out versus audience and developer expectations is a whole other story that should be distilled and told, but this is not the place for that.

Originally published in Third Person, edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin.

Spore grew from Will Wright’s fascination with the vastness of the universe, and the probability that it contains life. Wright linked Drake’s equation, which computes the probability of life occurring in the universe, with the long zoom of Eames’ Powers of Ten film. Each term in Drake’s equation corresponds to a different scale of the universe, and a different zoom of the Eames’ film. “Spore†stood for the spread of life through the universe: minute seeds of life hopping from one planet to another, either as bacteria riding comets, as panspermia theorizes, or intelligent beings on spaceships.

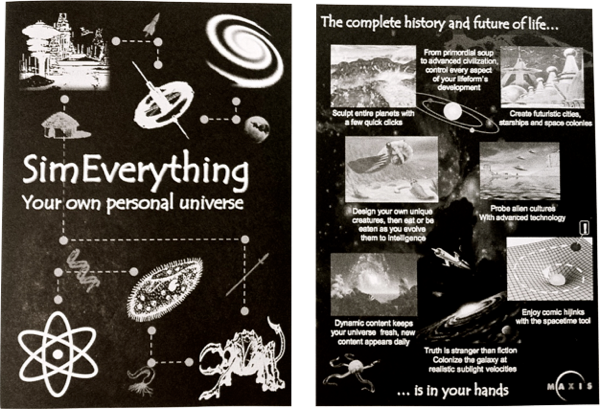

Early Spore prototypes and design concepts focused on simulating the movement and evolution of alien creatures, fluids, the birth of stars, galaxies, nebulae, and the spread of intelligent and non-intelligent life in media as small as a bread crumb, and as large as a galaxy. There was a galactic potter’s wheel, where you could try your hand at forming a stable spiral armed galaxy. A blind watchmaker interface allowed you to guide the evolution of novel life forms. You could sculpt huge piles of gas into stars that were just right for life. Will’s idea, at this point, was that players were to directly experience the difficulty and frustration of making life in the universe, and appreciate the improbability that life exists at all.

I initially joined the project at this early prototyping phase, when Spore was no more than a handful of people, and felt less like a game development project, and more of an awesome research and simulation endeavor. To me, the project was an intellectual love letter to all of existence, a depiction of the entire universe as a complex of interlocking self-similar systems. Patterns emerged ― everything, from disease to culture and space travel could be represented through some combination of cellular automata, agents, and networks. This was my summer dream job: make toys about anything in the universe, using everything I knew about interactive graphics and simulation, for the greatest simulation connoisseur in the world.

Of course, this isn’t quite the Spore everyone knows. There are two explanations for this, one is philosophical, and the other commercial. First, the commercial explanation. The Sims, Will’s previous game (The Sims Online was in production during Spore’s initial concept development), was one of the best selling games ever, and one of the most lucrative franchises in Electronic Art’s stable. The Sims was popular precisely because of how easily people could connect to it: you played with human beings living in suburban doll houses. Spore, by contrast, looked like it would become an awe inspiring existential crisis in a box, a toy universe so vast that it would take your breath away, not to mention your sense of self, time, and space. An acid trip on a compact disc, guaranteed to explode your brain, much like Kubrik’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey had blown a much younger Will Wright’s mind. Who was the target audience for Spore? Was it bigger than the market for SimEarth and SimLife? What changes would we have to make to appeal to players of The Sims?

The second, philosophical explanation, was also the design challenge: What would players identify and empathize with in Spore? Where were their characters? What would players do? Would anyone want to play a complicated game/art/science experiment? The entire universe is a vast, very heavy thing, and it wasn’t clear that people would be able to pick it up, and if they did, that it wouldn’t burn a hole through their hand, or head, for that matter.

I returned to Georgia Tech, to finish my masters degree, and said goodbye to Walnut Creek and my fellow universe prototypers: Will Wright, Jason Shankel, Ed Goldman, and Kees van Prooijen. I hadn’t spent much time working with most of them, since they had all been sucked onto the massive The Sims Online development team, including Ocean Quigley, who I wouldn’t meet until I returned in a little over a year.

When I came back, the team had roughly doubled in size, with some additions that put a new creative spin on Spore. Chris Trottier, a game designer who had spent years working on The Sims, had joined the project. Working with Will, Chris sought answers to some of life and Spore’s big questions: Who am I? What am I doing here? Why do I care?

New ideas were thrown into the design blender. Players would move through a sequential narrative, progressing through a handful of phases, corresponding to the evolution of life: creature, tribe, city, civilization, and finally outer space. The player was given a definite identity and point of view in each phase, structuring their motivations and activities. In creature game, for example, players would control an individual creature, as well as guiding the species’ evolution. Each phase corresponded, to some extent, to an existing game genre. As players progressed through Spore, their point of view and emotional investment would telescope, from individual creatures, to tribes, and civilizations. We would still blow peoples’ minds, but in a more structured, easier to understand sort of way.

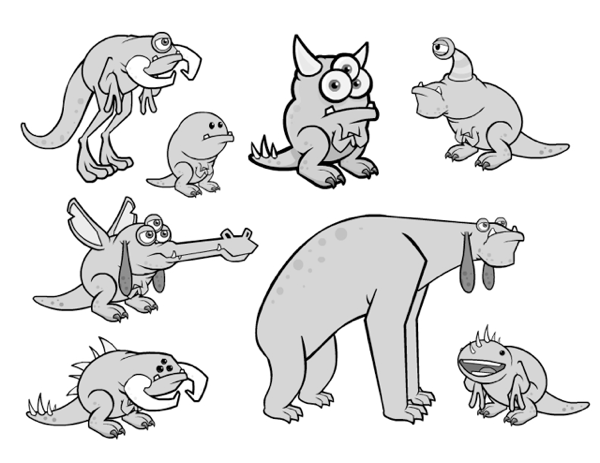

John Cimino, an artist and animator trained in the Disney tradition, had come onto the project, and started drawing pictures of strange yet adorable life forms. It was said that John’s cube was haunted by the the ghost of Jim Henson. Chris Trottier asked for pictures of aliens wearing sneakers. The “cute” team was born, balancing out the project’s already well developed “science” team. Over the next four years, these two teams grew and battled over Spore’s heart and sensibility, generating a dynamic balance that ensured Spore didn’t become another SimEarth, or The Jetsons, but something in between, epic yet accessible.

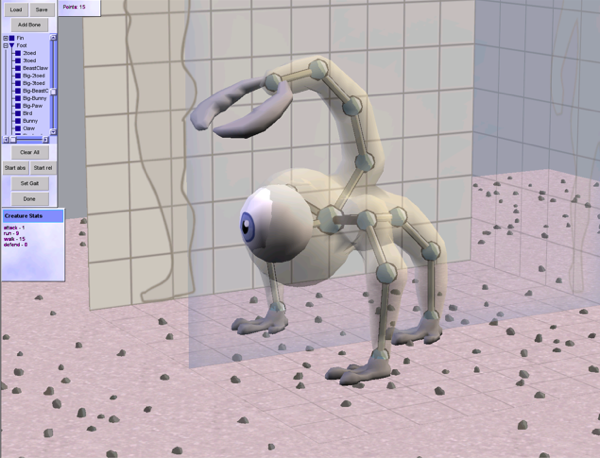

Player creativity became an integral part of the project. When I came back, Spore had a very primitive creature editor. You could draw creature skeletons, which would rattle to life and walk around. It was magic. Brad Smith, who interned the summer after I did, wrote Spore’s first creature editor, and Kees van Prooijen had written the logic to make whatever the player designed walk around.

The editor was clumsy, but it signified a new design direction: Spore was a game about enabling player creativity, and sharing those creations. The Sims had a sprawling online community which trafficked in player created stories, objects, and houses. Will wanted to build this kind of experience directly into the game, and worked it into Spore’s existing themes of evolution and exploration. By directing their creature’s evolution, players would contribute valuable material to the Spore gene pool, creating aliens and civilizations for other players to discover.

Players would design all kinds of things, like creatures, buildings, tools, vehicles, whatever, which would then be transparently pollinated from game to game. Thanks to the effort of other players, an infinite number of alien civilizations would await your discovery. The problem was going to be sorting through all this content, and figuring out what to put on players’ machines. You need a darn good librarian to recommend books to you if there are millions of books out there, and everyone has a private press. The other big problem was helping players make good creations. 3d modeling software is not for everyone, and besides, not everyone is a Picasso, or even a John Cimino. Brad and I spent the next several years designing and prototyping the fundamental features that became Spore’s entire suite of editors.

The reverberating vastness of Spore’s original concept became structured into a gentler, more appealing, experience through four design principles I’ll discuss below. Instead of becoming an abstract and intellectual game for astro-biologists and rocket scientists, Spore mutated into something more down to earth. You could explain the concept to almost anybody: make your own creature, take over the planet, and explore space, where you’ll meet space aliens made by other players. Who wouldn’t want to do that? In retrospect, the original inchoate vastness of Spore needed to be folded into a user friendly conformation, one that would invite ordinary people to pick it up and play.

Story

Spore’s early concept had no structured sense of time or sequence. Would players begin by forming a stable galaxy, stars, planets, and then set to creating life? Or perhaps they would evolve life on a planet, hit it with some asteroids, and try to get panspermia to happen? Like a universe before a creation myth, Spore had no obvious beginning, middle, or end. Deciding the game would move through a handful of stages, from cells to creatures, up through civilization, and then into space exploration, was crucial to getting the game concept to gel, at a high level.

Structured narratives are unusual for Maxis games, but Spore’s vast scope required a skeletal structure to hang the game off of. Besides, what story could be more appropriate than the evolution of life, and development of civilization? The story allowed both the developers and players to locate themselves in a narrative about the growth and expansion of life. It became possible to inhabit one phase of the game, and think about where you were coming from, and where you were off to. As developers, we could divide our efforts, and think about how the design grew out of the previous level, through this one, and into the next phase of the game. Even with this high level linear structure, Spore was still a monster project, in terms of scope. And, of course, by dividing our production effort into level based teams we set up any kind of inter-level design tradeoff and coordination to be an organizational hassle.

Point of View

Who am I? What am I doing here? What is expected of me? Why do I care? The problem is an awesome philosophical one: Who am I in this vast universe? What has meaning to me? How do I relate to the world, not through the conduit of an individual human being, but to Life, sprawled across billions of years? If we had made Spore into a God game, like SimEarth, SimCity, or The Sims, what would the player become emotionally invested in? The Sims invites players into its world through its characters, who inhabit places we recognize, and do things we care about, like eating, making love, working, and having fun. Sims face familiar problems: unrequited love, expensive but desirable consumer goods, and work/life balance. Biological diversity, evolutionary dead ends, atmospheric composition, and arms races might be real world problems, but they aren’t issues people easily relate to.

We placed a thread of life, billions of years long, into the player’s hands. Starting with a single cell, players are responsible for guiding an individual creature through its life. Sex, violence, and food are the creature’s primary concerns, which anyone can relate to. When a single generation ends, time telescopes, and the player shifts into the role of an intelligent designer of sorts, directing the genetic pathway of the species. The player’s point of view oscillates between individual creatures and the entire species. We found that players have no trouble emotionally investing themselves into this situation, even if they don’t immediately and intellectually grasp that their “self,” the creature they play, is a new individual each generation. As the game progresses, the player’s identity expands, from individuals, to tribes, and then onto civilizations. Once they’ve blasted off into space, players are again responsible for just one character, a cosmos cruising astronaut.

Then, there is the problem of aliens. Popular alien narratives focus on the friction of human/alien contact. E.T. entered a human world of suspicious and hostile adults. Familiar with War of The Worlds, the suspicious adults knew what to expect. But the really interesting design question about first contact that Spore posed is not the traditional one. Earthlings always identify with the home team, whether it’s humans fighting off space invaders, or a family going about its life in a Sims subdivision. The monster sales of The Sims demonstrated that earthling gamers overwhelmingly prefer to play with virtual human beings to the aliens, elves, and robots who populate most game worlds. The path to the mass market’s empathy, and dollars, it seems, is paved with asphalt, and goes directly to a suburban home populated by likable folks such as you and me. Spore’s dilemma was simple: people readily identify with people, but could we get them to do the same for aliens?

Creativity

Of course, these aren’t any old aliens we ask players to invest in — they’re your creation, your aliens. Once you start customizing, and design your creature, emotional investment is generated. It’s magic. Even the ugly ones are loved by their parents. Many games thrive on the interest generated by players’ creative investment. Console role playing games, for example, get this effect when players invest time in equipping and naming characters. I’ve always felt more attached to my characters as I fuss over their outfits and equipment. Creative interaction seems to always generate emotional involvement and attachment. Psychologically, it would seem that part of this stems from the sunk cost fallacy — we become attached to things we’ve invested time and energy into. Of course, it’s not just the hundreds of hours invested in a World of Warcraft character, their relationships, and possessions that generate attachment, it’s the sense that our fabrications are extensions of ourselves. As recipients of our attention and creative energy, our handiworks are reflections of who we are, tangible manifestations of our personalities. It’s no wonder we become attached to what we make, and take the success or failure of our own work and ideas very personally.

Spore neatly solves the alien attachment problem by asking the player to design them. If a player makes a creature, and it’s appealing, they’ll be quite invested in it. Reflecting on the success of The Sims Exchange, where players shared stories, characters, houses, and objects for The Sims, Will realized that shared creativity would give Spore a broader appeal. Why not build creative exchange into the game, rather than as a website that orbits it? Player created assets are constantly being uploaded and downloaded by Spore, enough material to fill a galaxy. There’s nothing like taking home your latest finger painting, and having mom hang it on the fridge for everyone to see. Sharing not only fills up the galaxy with cool stuff, but allows the entire world to see your fridge, motivating you to continue creating.

Of course, a lot of deep magic must work properly for something like Spore’s creature creator to function properly. It must be natural to use, easily producing satisfying results for anyone, from beginners to advanced users. And these aliens, lumps of polygons that no animator has ever seen before, must be brought to life. These are rather complicated endeavors, from a design, aesthetic, and technical point of view, but the player should never notice any of it. The game design implications are also challenging — the game must be playable and interesting, regardless of the creatures dropped into it.

Appeal

Disney animators understood that appeal didn’t just mean cute and cuddly characters, but “anything that a person likes to see, a quality of charm, pleasing design, simplicity, communication, and magnetism.” (p68, Thomas & Johnstone, The Illusion of Life).

Spore began life as an intellectual and scientific project. The team faced the challenge of maintaining the gravitas and realism of Will’s vision, while making the game as accessible and appealing as possible.

The decision to incorporate the character design aesthetic of an animator marked a turning point in the visual sensibility of the project. The genetic building blocks of Spore’s life forms, the creature parts, adopted the appeal and personality of John Cimino’s creature designs. And, imagining how Pixar might visually treat a film about bacteria, we put eyes on our single celled organisms. Our planets transformed into expansive landscapes, but retained a toy like sensibility. We made the galaxy more colorful. The entire team became vigilant, seeking opportunities to inject charm and wit into the project, producing the dry goofball humor that characterizes Maxis games.

Not that there was a mad rush for cartoony style, humor, and anthropomorphism. Each art review and design meeting had the potential to shift the balance of power between the “cute” and “science” teams, which is how we caricatured the opposed design sensibilities and their proponents. Spore’s style was a compromise worked out over many years between a scientific, realistic, and weighty aesthetic, and something popular, appealing, and full of personality.

By taking on these new design directions, the name “Spore” took on new meanings. In one sense, a spore is the germ of life, a basic reproductive element containing multiform organisms. Capable of withstanding extended hostile conditions, a spore can travel through the vast emptiness of space on a comet or asteroid, and bring the seed of life to a new world. We turned it into the genesis of Spore’s galactic narrative, marking the start of the player’s cosmic journey.

In another sense, the kaleidoscopic possibilities contained within a single spore are akin to Spore itself, and its enabling of player creativity. A vast galaxy of strange and wonderful aliens, civilizations, and planets await us, all unfolding from one tiny little seed. And like panspermia’s spores, which hop from planet to planet, pollinating the universe with life, player creations will migrate between worlds, traveling not on comets or asteroids, but on the internet, from computer to computer.

We’re trying to perform a scale inversion of cosmic proportions. Turn everything inside out: transform the huge, frightening, and awesome universe into something smooth, small, and delicate. A fragile seedling a child will hold and be charmed by. A smooth round seed, a game, which contains the vastness of the universe, the massive stampede of life, and the incomprehensible magnitudes of evolution.

Bibliography

Eames, Charles and Ray, Powers of Ten. Short documentary film, 1977. This film was prefigured by Cosmic View: The Universe in 40 jumps, by Kees Boeke, published in 1973.

Electronic Arts, Spore. 2008. Computer game.

Maxis, The Sims. Electronic Arts, 2000. Computer game.

Thomas and Johnstone, The Illusion of Life. New York: Hyperion, 1995.